|

No, it’s not 1, 2, 3 magic. And it has nothing to do with time outs. This approach goes beyond all that. This is about the real reason we set limits with our children: to help them (and sometimes to help us) to calm the &%#@ down! (okay, yes, and also to raise emotionally healthy, well-adjusted children). You know you don’t want to lose it and freak out on them (though, to be honest, we all lose it sometimes...more on that another time). But you also don’t want them running around like crazy people (there are not enough headphones and baths in this universe to keep you sane with that kind of chaos). So how do you let your kids be kids and also keep your cool? Last week I talked about noticing your desire to to set a limit is for yourself or for your child and the week before I talked about just how important letting them rough house play is to healthy emotional development. This week we get into the nitty gritty: How to actually set the limit. Hand in Hand Parenting suggests a 3-step formula: Listen Limit Listen 1- Listen to your child: what is s/he experiencing? Why? Listen within yourself: what’s the limit that will need to be set about, both for your and for your child. 2- Set the limit. Do it early. As soon as you notice your kid’s behavior is off track, move in close. Make eye contact. Offer your warmth, and your connection. Put your hand in the middle of whatever is going on. Set the limit. “I can’t let you hit your brother.” “I can’t let you have ice cream for breakfast.” 3- Listen again: What feelings in your child come up from having this limit set? Setting a limit with love and connection allows whatever ucky feelings that are getting in the way to come up to be released. Listen to them with love. “I can understand that sometimes you might want to hit your brother.” “I get that it would be fun to have ice cream for breakfast.” A plethora of research shows that when discipline includes listening with warmth in this way and the gentle, but firm setting of limits, children has more self-esteem, self-control, and resilience. Most of us did not have limits set in the way I am explaining here, so it might feel a bit (or A LOT) like swimming upstream at first. And, yes, it is a lot more work, which means parents need more support. But it pays off in the long run. Children whose parents listen with warmth as they express the feelings that come up when given a limit are able to regulate their emotions, delay gratification, and in general make better decisions for themselves later in life. They develop what Sam Goldstein and Robert Brooks in their book “Raising Resilient Children” call "the emotional clutch." So next time you feel the call to set a limit remember: Listen Limit Listen

0 Comments

You want to let your kids rough house. You know now the importance of that (if you missed that article click here). But you are worried about it getting out of hand. Our job as parents and teachers is to keep our children safe. But it is also to help them learn and grow. And growing involves some growing pains. How do we balance the needs for safety and challenge when our kids play rough? Last week I talked about the incredible importance of rough-and-tumble play for kids. This week we address how to tumble with our kids and to set limits when needed to keep it in that optimal risk zone (safe, but challenging and boundary-pushing). We need to balance the need for risk-taking with that for safety in three areas: their body, your body, and the environment. This week will focus on setting limits to keep your kidʼs body safe in rough-and-tumble play. Recently I was engaged in some intense foam sword fighting with two brothers in my play therapy office. The older brother loved to show off his moves and use his strength. Even though the younger brother looked overwhelmed and would sometimes get hurt, he wanted his brother to go hard on him. He needed it. In order to feel his strength he needed to be pushed to his limit. Itʼs my job to help him feel that inner strength. But it is also my job to keep him safe from harm. So imagine my dilemma when after saying he did not want his brother go easier on him, a piece of the foam sword broke off exposing the plastic underneath and grazed his neck causing a small scrape. Anxiety about if I am creating a safe enough environment for him, worry about what his parents might say, a desire to stop the game all together ran through my system in a millisecond. If I had listened to my own fear I would have stopped the game abruptly leaving him feeling weak and helpless once again. But instead I paused the game, really looked at his face that showed the pain but also strength, and asked if he would like to stop. He took a breath and said no, continuing on with a smile with his brother until they decided to stop on their own. The moral here: set limits from a place of keeping your kids safe from real danger, not from your own fear about if youʼre doing a good job. Your kids will thank you. Itʼs normal and healthy to want to protect our children. And it is true that play involves risk. But what research has shown is that allowing the natural course of some cuts and bruises and a few tears in play far exceeds the risks of cutting them off from this play (see the article on how stopping rough-and-tumble play can lead to violent tendencies). And even beyond allowing some hurts being okay, itʼs actually healing. When an adult lightly supervises rough-and-tumble play then they are there to listen to the hurts that open up when there is a cut or your child goes beyond her boundary and scares herself. All the scares or hurts from the day, the week, and even earlier in life can come out through those tears and into the loving heart of the caring adult that listens with patience and attention. This is the Hand in Hand Parenting Tool called Staylistening. So this week when you duke it out with your little ninja, remember to check in if you are setting a limit to truly keep them safe, or from your own place of worry or overwhelm.

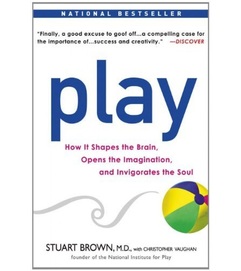

Want tips on how to deal with your own anxiety about chaotic play? Stay tuned for next weekʼs article or sign up here! Or schedule a consultation with me.  Kids need violent play. Although this statement may sound alarming (particularly form a child therapist) hear me out. Every day in my child therapy practice I hear children tell me how they weren’t allowed to pretend sword fight in school, or they can’t play superheroes, or they aren’t allowed to play tag because someone could get hurt. Although I understand teachers and parents are just trying to create peaceful environment, frankly these reports concern and upset me. I deeply want children to be able to feel safe emotionally and physically, to be kind to one another, to build healthy relationships, and to thrive in all areas … and the overwhelming evidence shows that if children are deprived of rough-and-tumble play these skills don’t develop properly.  Stuart Brown, MD is the founder of the National Institute of Play, researcher, and author. He has studied play and its effects for years. One of the most important findings he and his researchers have discovered is that when children are not allowed to engage in rough-and-tumble play (defined in his book as “play-fighting … and any activity that includes body contact among children…(including) superhero play” p.90), these children grew up to be antisocial and at times violent, including mass murderers (his first subject was the man who committed the Texas Tower Massacre). When the impulse to play was suppressed, these individuals were stripped of their natural method of learning such important social and emotional skills as empathy, boundaries, and self regulation.  In his pivotal and profound book, Play: How it Shapes Shapes the Brain, Opens the Imagination, and Invigorates the Soul Dr. Brown writes: “Research on rough-and-tumble play in animals and humans has shown that it is necessary for the development and maintenance of social awareness, cooperation, fairness, and altruism. Its nature and importance is generally unappreciated, particularly by preschool teachers or anxious parents, who often see normal rough-and-tumble play behavior such as hitting, diving, and wrestling (all done with a smile, between friends who stay friends) not as a state of play, but a state of anarchy that must be controlled.” (p.88) Parents and teachers are tasked with keeping children safe, and there is indeed risk in rough-house play. But what Dr. Brown discovered was that the benefits far outweighed the risk of scratches, hurt feelings, or even a broken bone here or there. He describes research on animal play that shows that when mammals are allowed natural play they are better able to socialize and make decisions, and those that are deprived of this play are stymied for life, unable to read social cues or deal with stress. We must help our children keep their bodies safe, but what of their spirit? We need to nourish that through this natural play as well. Empathy, the ability to set healthy boundaries, and to problem-solve stressful situations are developed when children are allowed lightly supervised rough-and-tumble play.  When a child runs after another child and pounces too hard, they get to see the effect that behavior had on their friend. The child cries, the pouncer feels bad and some part of him says, ‘I won’t do that again.’ This is how empathy is built. Brick by brick, pounce by pounce. And it’s also how boundaries are discovered and set. The child being pounced realizes what is too much and what is okay and learns how to communicate that. So the next time your child gets out his or her imaginary sword and cape, get yours out too, and let the tumbling begin. (Worried about how to set appropriate limits within rough play to keep it from crossing that line from healthy rough-housing into danger? Stay tuned for more on this next week…) |

AuthorKaren Wolfe, MFT is a psychotherapist in San Francisco and the East Bay. She is passionate about helping children and families thrive and has particular expertise with children with exceptional learning and sensory styles. Archives

August 2016

Categories

All

|

|

2354 Post St, Suite B,

San Francisco, 94115 |

3655 Grand Avenue,

Oakland, CA 94610 |

Greenwood Court,

Orinda, CA 94563 |